Blue plaque

A blue plaque is a permanent sign installed in a public place in the United Kingdom, and certain other countries and territories, to commemorate a link between that location and a famous person, event, or former building on the site, serving as a historical marker.

The term is used in the United Kingdom in two senses. It may be used narrowly and specifically to refer to the "official" scheme administered by English Heritage, and for much of its history restricted to sites within Greater London; or it may be used less formally to encompass a number of similar schemes administered by organisations throughout the UK. The plaques erected are made in a variety of designs, shapes, materials and colours: some are blue, others are not. However, the term "blue plaque" is often used informally to encompass all such schemes.

History

[edit]The "official" scheme traces its origins to that launched in 1866 in London, on the initiative of the politician William Ewart, to mark the homes and workplaces of famous people.[3][4] The first such scheme in the world, it has directly or indirectly provided the inspiration and model for many others. The scheme has been administered successively by the Society of Arts (1866–1901), the London County Council (1901–1965), the Greater London Council (1965–1986) and English Heritage (1986 to date). It was initially focused on Greater London, although between 1998 and 2005, under a trial programme since discontinued, 34 plaques were erected elsewhere in England. The Levelling-up and Regeneration Act 2023 extended the scheme to the whole of England.[5]

Many other plaque schemes have been initiated in the United Kingdom. Some are restricted to a specific geographical area, others to a particular theme of historical commemoration. They are administered by a range of bodies including local authorities, civic societies, residents' associations and other organisations such as the Transport Trust, the Royal Society of Chemistry, the Music Hall Guild of Great Britain and America and the British Comic Society.

There are also commemorative plaque schemes throughout the world such as those in Paris, Rome, Oslo, and Dublin; and in other cities in Australia, Canada, the Philippines, Russia, and the United States. These take various forms, and they are more likely to be known as commemorative plaques or historical markers.

English Heritage scheme

[edit]

The original blue plaque scheme was established by the Society of Arts in 1867, and since 1986 has been run by English Heritage. It is the oldest such scheme in the world.[3][4]

After being conceived by politician William Ewart in 1863, the scheme was initiated in 1866 by Ewart, Henry Cole and the Society of Arts (now the Royal Society of Arts),[8] which erected plaques in a variety of shapes and colours.

The first plaque was unveiled in 1867 to commemorate Lord Byron at his birthplace, 24 Holles Street, Cavendish Square. This house was demolished in 1889. The earliest blue plaque to survive, also put up in 1867, commemorates Napoleon III in King Street, St James's.[4] Byron's plaque was blue, but the colour was changed by the manufacturer Minton, Hollins & Co to chocolate brown to save money.[9] The first woman to be honoured with a plaque was the actor Sarah Siddons in 1876.[10] The plaque, placed on her house in Marylebone, London, was retrieved when the house was demolished in 1905 and is now held in the Victoria and Albert Museum.[11]

In total, the Society of Arts put up 35 plaques, fewer than half of which survive today. The Society only erected one plaque within the square-mile of the City of London, that to Samuel Johnson on his house in Gough Square, in 1876. In 1879, it was agreed that the City of London Corporation would be responsible for erecting plaques within the City to recognise its jurisdictional independence. This demarcation has remained ever since.[4]

In 1901, the Society of Arts scheme was taken over by the London County Council (LCC),[3] which gave much thought to the future design of the plaques. It was eventually decided to keep the basic shape and design of the Society's plaques, but to make them uniformly blue, with a laurel wreath and the LCC's title.[12] Though this design was used consistently from 1903 to 1938, some experimentation occurred in the 1920s, and plaques were made in bronze, stone and lead. Shape and colour also varied.[12]

In 1921, the most common (blue) plaque design was revised, as it was discovered that glazed Royal Doulton stoneware was cheaper than the encaustic formerly used. In 1938, a new plaque design was prepared by an unnamed student at the LCC's Central School of Arts and Crafts and was approved by the committee. It omitted the decorative elements of earlier plaque designs, and allowed for lettering to be better spaced and enlarged. A white border was added to the design shortly after, and this has remained the standard ever since.[9] No plaques were erected between 1915 and 1919, or between 1940 and 1947, owing to the two world wars.[13] The LCC formalised the selection criteria for the scheme in 1954.[4]

When the LCC was abolished in 1965, the scheme was taken over by the Greater London Council (GLC). The principles of the scheme changed little, but now applied to the entire, much larger, administrative county of Greater London. The GLC was also keen to broaden the range of people commemorated. The GLC erected 252 plaques, the subjects including Sylvia Pankhurst,[14] Samuel Coleridge-Taylor,[15] and Mary Seacole.[16]

In 1986, the GLC was disbanded and the blue plaques scheme passed to English Heritage. English Heritage erected more than 300 plaques in London. In January 2013 English Heritage suspended proposals for plaques owing to funding cuts.[13][17] The National Trust's chairman stated that his organisation might step in to save the scheme.[18] In the event the scheme was relaunched by English Heritage in June 2014 with private funding (including support from a new donors' club, the Blue Plaques Club, and from property developer David Pearl).[19] Four members of the advisory panel resigned over this transmutation. Professor David Edgerton and author and critic Gillian Darley were concerned that the scheme had been "reduced to a marketing tool for English Heritage".[20] The vice chair Dr Celina Fox and Dr Margaret Pelling stated that the scheme was "being dismantled and its previous achievements discredited".[21]

In April 2015, English Heritage was divided into two parts, Historic England (a statutory body), and the new English Heritage Trust (a charity, which took over the English Heritage operating name and logo). Responsibility for the blue plaque scheme passed to the English Heritage Trust.

The 1,000th plaque, marking the offices of the Women's Freedom League, 1908–1915, was unveiled in 2023.[22]

-

Society of Arts plaque on Samuel Johnson's house in Gough Square, London (erected 1876). Many of the early Society of Arts and LCC plaques were brown in colour.

-

London County Council bronze plaque in Canonbury Square, commemorating Samuel Phelps (erected 1901)

-

London County Council plaque at 48 Doughty Street, Holborn, commemorating Charles Dickens (erected 1903)

-

One of seven LCC Royal Doulton plaques with coloured laurel relief border erected in 1925; 41 Beak Street, Soho

-

London County Council plaque at 100 Lambeth Road, Lambeth, commemorating William Bligh (erected 1952)

-

Greater London Council plaque at 29 Fitzroy Square, Fitzrovia, commemorating Virginia Woolf (erected 1974)

-

English Heritage plaque, at 22b Ebury Street, Belgravia, London, commemorating Ian Fleming (erected 1996)

Criteria

[edit]To be eligible for an English Heritage blue plaque in London, the famous person concerned must:[23]

- Have been dead for 20 years or have passed the centenary of their birth. Fictional characters are not eligible;

- Be considered eminent by a majority of members of their own profession; have made an outstanding contribution to human welfare or happiness;

- Have lived or worked in that building in London (excluding the City of London and Whitehall) for a significant period, in time or importance, within their life and work; be recognisable to the well-informed passer-by, or deserve national recognition.

In cases of foreigners and overseas visitors, candidates should be of international reputation or significant standing in their own country.

With regards to the location of a plaque:

- Plaques can only be erected on the actual building inhabited by a figure, not the site where the building once stood, or on buildings that have been radically altered;

- Plaques are not placed onto boundary walls, gate piers, educational or ecclesiastic buildings, or the Inns of Court;

- Buildings marked with plaques should be visible from the public highway;

- A single person may not be commemorated with more than one blue plaque in London.[23]

Other schemes have different criteria, which are often less restrictive: in particular, it is common under other schemes for plaques to be erected to mark the sites of demolished buildings.

Selection process

[edit]

Almost all the proposals for English Heritage blue plaques are made by members of the public who write or email the organisation before submitting a formal proposal.[25]

English Heritage's in-house historian researches the proposal, and the Blue Plaques Panel advises on which suggestions should be successful. This is composed of 12 people from various disciplines from across the country. The panel is chaired by Professor William Whyte. Other members (as at September 2023) include Richard J. Aldrich, Mihir Bose, Andrew Graham-Dixon, Claire Harman, Gus Casely-Hayford and Amy Lame.[26] The actor and broadcaster Stephen Fry was formerly a member of the panel, and wrote the foreword to the book Lived in London: Blue Plaques and the Stories Behind Them (2009).[27]

Roughly a third of proposals are approved in principle, and are placed on a shortlist. Because the scheme is so popular, and because a lot of detailed research has to be carried out, it takes about three years for each case to reach the top of the shortlist. Proposals not taken forward can only be re-proposed once 10 years have elapsed.[23]

Manufacture

[edit]From 1923, soon after the standardisation of the design in 1921, the plaques were manufactured by Royal Doulton which continued their production until 1955.[28] From 1984 until 2015 they were made by Frank Ashworth at his studio in Cornwall, and were then inscribed by his wife.[29] From 1955 to 1985 the lettering for the plaques was designed in the Roman lettering style by Henry Hooper.[30][31] Since 2015, the plaques have been made by Ned Heywood, a potter, at his workshop in Chepstow, Wales.[22] Each plaque is made entirely by hand.[32][33]

Event plaques

[edit]

A small minority of GLC and English Heritage plaques have been erected to commemorate events which took place at particular locations rather than the famous people who lived there.

Outside London

[edit]In 1998, English Heritage initiated a trial national plaques scheme, and over the following years erected 34 plaques in Birmingham, Merseyside, Southampton and Portsmouth. The scheme was discontinued in 2005, although English Heritage continued to provide advice and guidance to individuals and organisations outside of London wanting to develop local schemes.[35]

In September 2023 the Department for Culture, Media and Sport announced the reintroduction of a national scheme, with Historic England as the lead developer.[36] From mid 2024, the public will be invited to submit nominations, with eligibility criteria including a minimum of 20 years having passed since the death of the nominee, who must have made a significant contribution to human welfare or happiness. At least one surviving building must be associated with the nominee in a form that they would have recognised and the building must be visible from the public highway.[37] The first plaque in the scheme was unveiled in Ilkley, West Yorkshire on 23 February 2024, commemorating Daphne Steele, first Black matron in the National Health Service in 1964.[38] On 24 May 2024, a blue plaque commemorating the childhood home of musician George Harrison in Liverpool was unveiled, and was referred to in the press as "Historic England's first official non-London blue plaque".[39]

Other schemes

[edit]The popularity of English Heritage's London blue plaques scheme has meant that a number of comparable schemes have been established elsewhere in the United Kingdom. Many of these schemes also use blue plaques, often manufactured in metal or plastic rather than the ceramic used in London, but some feature plaques of different colours and shapes. In 2012, English Heritage published a register of plaque schemes run by other organisations across England.[40]

The criteria for selection varies greatly. Many schemes treat plaques primarily as memorials and place them on the sites of former buildings, in contrast to the strict English Heritage policy of only installing a plaque on the actual building in which a famous person lived or an event took place.

London

[edit]The Corporation of London continues to run its own plaque scheme for the City of London, where English Heritage does not erect plaques. City of London plaques are blue and ceramic, but are rectangular in shape and carry the City of London coat of arms.[4][41] Because of the rapidity of change in the built environment within the City, a high proportion of Corporation of London plaques mark the sites of former buildings.

Many of the 32 London boroughs also now have their own schemes, running alongside the English Heritage scheme. Westminster City Council runs a green plaque scheme, each plaque being sponsored by a group with a particular interest in its subject.[42] The London Borough of Southwark started its own blue plaque scheme in 2003, under which the borough awards plaques through popular vote following public nomination: living people may be commemorated.[43] The London Borough of Islington has a similar green heritage plaque scheme, initiated in 2010.[44]

Other plaques may be erected by smaller groups, such as residents' associations. In 2007 the Hampstead Garden Suburb Residents Association erected a blue plaque in memory of Prime Minister Harold Wilson at 12 Southway as part of the suburb's centenary celebrations.

-

City of Westminster green plaque at 18 Cavendish Square, Marylebone, commemorating Josef Dallos, contact lens pioneer (erected 2010)

-

Corporation of London plaque on the site of John Keats' birthplace

-

City of Westminster green plaque commemorating Laura Ashley

-

City of Westminster green plaque at the Savoy Theatre, the first public building in the world to be lit entirely by electricity when it was fitted with the incandescent light bulb developed by Sir Joseph Swan in 1881.[45]

England

[edit]| Location | Details |

|---|---|

| Aldershot | In 2017 in Aldershot in Hampshire the Aldershot Civic Society unveiled its first blue plaque to comedian and actor Arthur English at the house where he had been born. It is intended that this will be the first in a series dedicated to notable local people or historic buildings.[46][47][48] |

| Berkhamsted | The Hertfordshire town of Berkhamsted unveiled a set of 32 blue plaques in 2000 on some of the town's most significant buildings,[49] including Berkhamsted Castle, the birthplace of writer Graham Greene and buildings associated with the poet William Cowper, John Incent (a Dean of St. Paul's Cathedral) and Clementine Churchill. The plaques feature in a Heritage Trail promoted by the town's council.[50] |

| Birmingham | The Birmingham Civic Society provides a blue plaque scheme in and around Birmingham: there are over 90 plaques commemorating notable former Birmingham residents and historical places of interest.[51][52] |

| Boston, Lincolnshire | The Boston Preservation Trust provides a blue plaque scheme in and around Boston, Lincolnshire: there are over 27 plaques commemorating notable former Boston residents and historical places of interest.[53] |

| Bournemouth | Bournemouth Borough Council has unveiled more than 30 blue plaques.[54] Its first plaque was unveiled on 31 October 1937 to Lewis Tregonwell, who built the first house in what is now Bournemouth. Two further plaques followed in 1957 and 1975 to writer Robert Louis Stevenson and poet Rupert Brooke respectively. The first blue plaque was unveiled on 30 June 1985 dedicated to Sir Percy Shelley, 3rd Baronet.[55] |

| Derbyshire | In 2010, Derbyshire County Council allowed its residents to vote via the Internet on a shortlist of notable historical figures to be commemorated in a local blue plaque scheme.[56] The first six plaques commemorated industrialist Richard Arkwright junior (Bakewell), Olave Baden-Powell and the "Father of Railways" George Stephenson (Chesterfield), the mathematical prodigy Jedediah Buxton (Elmton), actor Arthur Lowe (Hayfield), and architect Joseph Paxton (Chatsworth House).[57] |

| Gateshead | A long-running blue plaque scheme is in operation in Gateshead. Run by the council, the scheme was registered with English Heritage in 1970[40] and 29 blue plaques were installed between the inception of the scheme in 1977 and the publication of a commemorative document in 2010.[58][59] The Gateshead scheme aims to highlight notable persons who lived in the borough, notable buildings within it and important historical events.[60] Some of those commemorated through the scheme include Geordie Ridley, author of the "Blaydon Races":[61] William Wailes, a 19th-century proponent of stained glass;[62][63] the industrialist and co-founder of Clarke Chapman, William Clarke[64] and Sir Joseph Swan, inventor of the incandescent light bulb.[64][65] More recent plaques (both erected in 2012) have commemorated Vincent Litchfield Raven, the chief mechanical engineer at the North Eastern Railway;[66] and the 19th-century Felling mining disasters.[67] |

| Leeds | Leeds Civic Trust started its blue plaque scheme in 1987 and by 2020 had 180 plaques.[68] |

| Loughton | The Essex town of Loughton inaugurated a scheme in 1997 following a programme allowing for three new plaques a year; 42 had been erected by 2019. The aim is to stimulate public interest in the town's heritage.[69] Among the Loughton blue plaques is that to Mary Anne Clarke, which is in fact a pair of identical plaques, one on the back, and one on the front, of her house, Loughton Lodge. |

| Malvern | In 2005, Malvern Civic Society and Malvern Hills District council announced that blue plaques would be placed on buildings in Malvern that were associated with famous people, including Franklin D. Roosevelt. Since then blue plaques have been erected to commemorate C. S. Lewis, Florence Nightingale, Charles Darwin and Haile Selassie.[70][71][72] |

| Manchester | A scheme in Manchester is co-ordinated by Manchester Art Gallery, to whom nominations can be submitted. Plaques must be funded by those who propose them.[73][74] From 1960 to 1984 all plaques were ceramic, and blue in colour. From 1985, they were made of cast aluminium, colour-coded to reflect the type of commemoration (blue for people; red for events in the city's social history; black for buildings of architectural or historic interest; green for other subjects). After a period of abeyance, the scheme has been revived and all plaques are now patinated bronze.[73] |

| Oldham | A blue plaque at Oldham's Tommyfield Market (Greater Manchester) marks the 1860s origin of the fish and chip shop and fast food industries. |

| Oxfordshire | The Oxfordshire Blue Plaques Board places plaques in the city of Oxford and elsewhere in the county.[75] |

| Ringwood | The Ringwood Society installed the first blue plaque in the town in 1978, to commemorate the Monmouth Rebellion.[76] |

| Southampton | Starting in 2004, English Heritage installed several blue plaques "to commemorate famous or well-loved people who have contributed significantly to Britain and Southampton's history... Many other plaques have been put up by friends, family and fans of Southampton's most influential people and historic places".[77] Since 2022, The Spitfire Makers Charitable Trust has been installing blue plaques to commemorate sites of Spitfire production in Southampton and Hampshire.[78] |

| Sunderland | Sunderland now has over 70 commemorative blue plaques spread throughout the city of Sunderland, marking buildings, places of interest or influential people with connections to the area.[79] |

| Swindon | Swindon Heritage installs blue plaques in Swindon to commemorate the famous people, places and events which are part of the town's history. These are financed through public donations from individuals and groups. The first plaque to be unveiled was to the suffragette Edith New in March 2016. Others commemorated include the writer and naturalist Richard Jefferies the actress Diana Dors.[80] |

| Tameside | Throughout Tameside Blue and Brown Plaques commemorate local people and places of historical importance. Artists, poets, botanists and war heroes are among those celebrated.[81] |

| Wolverhampton | Wolverhampton has over 90 blue plaques erected by The Wolverhampton Society in a scheme which was started in 1983 by the then Wolverhampton Civic Society.[82] One of the more unusual plaques marks the location of the World Altitude Balloon Record on Friday 5 September 1862.

In 2021, a Black Lives Matter plaque was erected at the Wolverhampton Heritage Centre (the former constituency office of Enoch Powell, where his Rivers of Blood speech was written) to commemorate immigrant rights activist Paulette Wilson, a member of the Windrush generation.[83][84][85] |

| York | York Civic Trust has operated a blue plaque scheme since the 1940s.[86] Plaques erected by the Trust use a variety of shapes and materials, including bronze, wood, slate, aluminium, and glass, and commemorate buildings and events as well as people.[86] All plaques bear the emblem of the Civic Trust, which is based on the York assay mark of 1423.[86] |

-

A Gateshead blue plaque commemorating William Clarke, co-founder of the engineering firm Clarke Chapman.

-

The first Swindon Heritage blue plaque, commemorating suffragette Edith New, who was one of the first two suffragettes to use vandalism as a tactic.

-

Oxfordshire blue plaque commemorating the first sub-4-minute mile run by Roger Bannister on 6 May 1954 at the University of Oxford's Iffley Road track.

-

Blue plaque in Shirley, Southampton which commemorates the contribution of Sun Engineering Ltd towards building the Spitfire.

Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland

[edit]In Northern Ireland, Belfast City Council and the Ulster History Circle are among a small number of groups administering blue plaques.[87] Established in 1983, the Ulster History Circle has erected around 260.[88][89] Its scope extends into the Republic of Ireland, covering all nine counties of Ulster, the northern province in Ireland.[90] Elsewhere in the Republic, schemes are operated through local authorities[91] and civic societies.[92]

Scotland

[edit]Historic Environment Scotland, the Scottish heritage agency, has previously operated a national commemorative plaques scheme but, as of 2023, this was inactive.[93] Regional schemes are run by local authorities.[94][95]

Wales

[edit]Wales does not operate a national blue plaque scheme, although in 2022 Andrew RT Davies, leader of the Welsh Conservative Group in the Senedd, called for the introduction of a country-wide approach.[96] Regional schemes are operated by local authorities such as Swansea[97][98] and civic societies.[99] The Purple Plaques scheme is a national scheme (across Wales) that aims to commemorate women whose lives have had a significant and long-lasting impact.

Individual examples

[edit]-

Blue plaque in Rhiwbina Garden Village commemorating Iorwerth Peate, first director of St Fagans National Museum of History

Thematic schemes

[edit]There also exist several nationwide schemes sponsored by special-interest bodies, which erect plaques at sites or buildings with historical associations within their particular sphere of activity.

- The Transport Trust's Red Wheel scheme erects red plaques on sites of significance in the evolution of transport.[100]

- The Music Hall Guild of Great Britain and America erects blue plaques on sites associated with notable music hall and variety artistes, mainly in the London area.

- The British Comedy Society (previously known as the Dead Comics' Society) erects blue plaques on the former homes of well-known comedians, including those of Sid James and John Le Mesurier.

- The Royal Society of Chemistry's Chemical Landmark Scheme erects hexagonal blue plaques to mark sites where the chemical sciences are considered to have made a significant contribution to health, wealth, or quality of life.[101]

- The Institute of Physics installs circular blue plaques to celebrate physicists' lives or work at various locations in the Great Britain and Ireland. Plaques exist in Edinburgh for Thomas Henderson and Thomas David Anderson, at Glasgow for Alexander Wilson and William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin, at Eskdalemuir Observatory for Lewis Fry Richardson, at the birthplace of Charles Thomson Rees Wilson in the Pentland Hills, at Leeds for William Henry Bragg and at Aberdeen for George Paget Thomson.[102] In 2015, Peter Higgs unveiled his own plaque, installed on the building in which he had predicted the Higgs boson.[103]

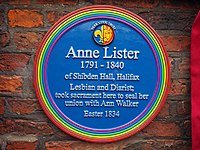

- Rainbow plaques commemorate LGBT people, events or sites. They have been erected by different bodies, but are distinguished by having rainbow colours around the circumference.[104][105]

-

Transport Trust plaque at Hythe Pier and Railway, Hythe, Hampshire, the oldest working pier railway in the world

-

Comic Heritage plaque commemorating Harry Worth at the site of the former Teddington Studios, Greater London

-

Royal Society of Chemistry plaque on the Chemistry Department of University College London, recording the work carried out there by Sir Christopher Ingold (erected 2008)

-

Institute of Physics plaque on the Parkinson Building, University of Leeds, recording the work carried out there by Sir William Henry Bragg

-

Rainbow plaque outside Holy Trinity Church, Goodramgate, York, erected by York Civic Trust in 2018 to commemorate Anne Lister and Ann Walker

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Alfred Tennyson | Poet | Blue Plaques". English Heritage. Retrieved 17 January 2023.

- ^ Cantopher, Will (May 2011). "Bob Marley's London Life on 30th Anniversary of Death". BBC News. Archived from the original on 13 January 2019. Retrieved 15 June 2024.

- ^ a b c Spencer, Howard (2008). "The commemoration of historians under the blue plaque scheme in London". Institute of Historical Research. Retrieved 16 June 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f "The History of Blue Plaques". English Heritage. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ "National expansion of blue plaques schemes". GOV.UK. Department for Culture, Media and Sport. 6 September 2023. Retrieved 3 April 2024.

- ^ "Plaque Honours Memories of Marley". BBC News. 26 October 2006. Archived from the original on 22 November 2008. Retrieved 15 June 2024.

- ^ Cantopher, Will (May 2011). "Bob Marley's London Life on 30th Anniversary of Death". BBC News. Archived from the original on 13 January 2019. Retrieved 15 June 2024.

- ^ Hansard vol 172 17 July 1863 quoted in 'The commemoration of historians under the blue plaque scheme in London' by author Howard Spencer

- ^ a b "About blue plaques". Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Retrieved 16 June 2011.

- ^ Brown, Mark (30 October 2018). "English Heritage calls for female Blue plaque nominees". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- ^ "Sarah Siddons lost plaque". London Remembers. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- ^ a b "The Blue Plaque Design". English Heritage. Retrieved 16 June 2011.

- ^ a b Quinn, Ben (6 January 2013). "Blue plaques scheme suspended after 34% cut in government funding". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- ^ Plaque #473 on Open Plaques

- ^ Plaque #136 on Open Plaques

- ^ Plaque #604 on Open Plaques

- ^ "Blue Plaques scheme position statement". 8 January 2013. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- ^ Gray, Louise (7 January 2013). "National Trust could save blue plaques". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022.

- ^ "London Blue Plaques Re-Open For Nominations – 18 June 2014". English Heritage. Retrieved 27 June 2014.

- ^ "London Blue Plaques scheme re-launched", Salon: Society of Antiquaries of London Online Newsletter, 322, 23 June 2014, retrieved 27 June 2014

- ^ Celina Fox (5 July 2014). "Implacable blue plaque cuts". The Observer. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- ^ a b Kirka, Danica (19 September 2023). "London's historic blue plaques seek more diversity as 1,000th marker is unveiled". World News. Associated Press News. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- ^ a b c "Propose a plaque". English Heritage. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- ^ Plaque #1412 on Open Plaques

- ^ "How to propose a Blue Plaque". Retrieved 7 July 2011.

- ^ "Blue Plaques Panel". English Heritage. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- ^ Parker, Peter (11 July 2009). "Lived in London: Blue Plaques and the Stories Behind Them by Emily Cole: review". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 7 July 2010.

- ^ "The changing face of the Blue Plaque". English Heritage. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- ^ "Built to last: the making of a blue plaque". English Heritage. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- ^ Gibbs, Jon (23 March 2005). "Obituary: Henry Hooper". The Independent. Retrieved 21 September 2023.

- ^ Gibbs, Jon (2005). "Henry Hooper: Lettering Craftsman". The Edward Johnston Foundation Journal: 3–8.

- ^ Misbahuddin, Sameena (19 September 2023). "Blue plaque scheme celebrates major milestone". BBC News. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- ^ "Blue plaques". Ned Heywood. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- ^ Plaque #517 on Open Plaques

- ^ "About Blue Plaques: Frequently Asked Questions". English Heritage. Archived from the original on 17 May 2015. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- ^ "National Blue Plaques Scheme". Historic England. 6 September 2023. Retrieved 15 October 2023.

- ^ "First black NHS matron, Beatles icon and pioneering ceramist to receive first official blue plaques outside London". Department for Culture, Media and Sport. 23 February 2024. Retrieved 25 February 2024.

- ^ "Daphne Steele (1927 to 2004)". Department for Culture, Media and Sport. 23 February 2024. Retrieved 25 February 2024.

- ^ Cunningham, Ed (24 May 2024). "The UK's first blue plaque outside London has been revealed". Time Out. Archived from the original on 24 May 2024. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ a b "Register of Plaque Schemes". English Heritage. Archived from the original on 2 January 2015. Retrieved 16 July 2012.

- ^ "Blue plaques". City of London. Archived from the original on 21 May 2015. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ^ "Green Plaques Scheme". Archived from the original on 16 July 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2011.

- ^ "Blue Plaque Winners 2007". Southwark Borough Council. Archived from the original on 13 September 2008.

- ^ "Recent Plaques". London Borough of Islington. Archived from the original on 22 March 2015. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ^ "A tour of Michael Faraday in London". Royal Institution. Retrieved 10 July 2024.

- ^ "Blue Plaque for Arthur English – Aldershot Civic Society website". Archived from the original on 28 January 2018. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- ^ 'Are You Being Served? actor Arthur English honoured with blue plaque' – BBC News Online – 15 July 2017

- ^ 'Blue plaque unveiled for Aldershot's Arthur English' – Eagle Radio – 15 July 2017

- ^ "The history of Berkhamsted". Berkhamsted Town Council. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 6 May 2011.

- ^ Cook, John (2009). A Glimpse of our History: a short guided tour of Berkhamsted (PDF). Berkhamsted Town Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 6 May 2011.

- ^ "Birmingham Civic Society plaques list". Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- ^ "Birmingham Civic Society Awards". Archived from the original on 2 July 2014. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "Heritage Trail". Boston Preservation Trust. Retrieved 6 January 2025.

- ^ "Blue Plaques in Bournemouth". Archived from the original on 22 March 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2011.

- ^ "Blue Plaques of Bournemouth". Bournemouth Borough Council. Archived from the original on 30 October 2012. Retrieved 12 November 2010.

- ^ "Final vote for Derbyshire blue plaque honour". BBC News. 25 April 2010. Retrieved 6 May 2011.

- ^ "Blue Plaques". Derbyshire County Council. Retrieved 6 May 2011.

- ^ "Commemorative Plaques". Gateshead Council. 2012. Archived from the original on 8 September 2012. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- ^ Richards, Linda (9 September 2010). "Blue Plaques mapshows off famous spots". Newcastle Evening Chronicle. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- ^ "Gateshead's Commemorative Plaques" (PDF). Gateshead Council. June 2012. Retrieved 29 December 2012. at p.2

- ^ "Gateshead's Commemorative Plaques" (PDF). Gateshead Council. June 2012. Retrieved 29 December 2012. at p.3

- ^ "Plaque honours famous ex-resident". the BBC. 15 June 2005. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- ^ "Fairytale mansion gets new life". BBC. 14 July 2004. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- ^ a b "Gateshead's Commemorative Plaques" (PDF). Gateshead Council. June 2012. Retrieved 29 December 2012. at p.8

- ^ "Gateshead Blue Plaques – Joseph Swan 1828–1914". Gateshead Libraries. 2011. Archived from the original on 27 January 2013. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- ^ Wainwright, Martin (21 March 2012). "Gateshead honours an engineering giant whose genius has lessons for our times". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- ^ "Felling Pit Disaster remembered on 200th anniversary". the BBC. 25 May 2012. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- ^ Grady, Kevin; Tyrell, Robert (2020). Blue Plaques of Leeds The Next Collection. Leeds: Leeds Civic Trust. ISBN 978-0-905671-99-4.

- ^ "Loughton Blue Plaques" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 August 2016. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- ^ "Blue plaque link to town's famous faces". Malvern Gazette. Newsquest Media Group. 21 October 2005. Retrieved 25 June 2011.

- ^ "Plaque a tribute to Narnia author". Malvern Gazette. Newsquest Media Group. 21 July 2006. Retrieved 25 June 2011.

- ^ "Emperor will be remembered as part of civic week". Malvern Gazette. Newsquest Media Group. 6 June 2011. Retrieved 25 June 2011.

- ^ a b "Commemorative Plaques". Manchester City Council. Retrieved 7 July 2011.

- ^ "Commemorative plaques scheme". Manchester Art Gallery. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- ^ "Oxfordshire Blue Plaques Scheme". www.oxonblueplaques.org.uk. Retrieved 19 July 2022.

- ^ "Ringwood Blue Plaque Scheme". The Ringwood Society. Retrieved 28 September 2023.

- ^ "Blue plaques around Southampton". Southampton City Council. Retrieved 5 August 2024.

- ^ "The Commemorative Plaques Project". The Spitfire Makers Charitable Trust. 9 November 2020. Retrieved 5 August 2024.

- ^ "Heritage blue plaques". Sunderland City Council. Retrieved 6 January 2025.

- ^ "SWINDON HERITAGE BLUE PLAQUES". SWINDON HERITAGE BLUE PLAQUES. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- ^ "Tameside Blue Plaques - Tameside MBC". www.tameside.gov.uk. Retrieved 6 January 2025.

- ^ "Blue Plaques". The Wolverhampton Society. Retrieved 30 April 2024.

- ^ "Plaque for Windrush campaigner unveiled at former office of Enoch Powell". The Guardian. 22 June 2021. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ^ Vukmirovic, James (22 June 2021). "Paulette Wilson: Windrush campaigner's life honoured with ceremony and plaque". www.expressandstar.com. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ^ "Paulette Wilson, late Windrush campaigner, to be honoured with blue plaque". The Independent. 22 June 2021. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ^ a b c "Civic Trust Plaques – York Civic Trust". yorkcivictrust.co.uk. Retrieved 19 July 2022.

- ^ "Poet and broadcaster remembered". 8 February 2011. Archived from the original on 21 March 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2011.

- ^ "THe Ulster History Circle". Archived from the original on 9 July 2011. Retrieved 7 July 2011.

- ^ Ulster History Circle: Existing Plaques. https://ulsterhistorycircle.org.uk/existing-plaques/

- ^ "Official website". Ulster History Circle. Retrieved 10 October 2023.

- ^ "Commemorative Plaques Scheme". Dublin City Council. 30 October 2020. Retrieved 10 October 2023.

- ^ "Blue plaques". Waterford Civic Trust. Retrieved 10 October 2023.

- ^ "Commemorative Plaque Scheme". Historic Environment Scotland. Retrieved 20 September 2023.

- ^ "Commemorative Plaques". Aberdeen City Council. 14 September 2021. Retrieved 20 September 2023.

- ^ "Blue Plaques" (PDF). Jedburgh and District Community Group. Retrieved 20 September 2023.

- ^ "Andrew RT Davies calls for national blue plaque scheme for Wales". Nation.Cymru. 2 August 2022. Retrieved 20 September 2023.

- ^ "Swansea blue plaques". Swansea Council. Retrieved 20 September 2023.

- ^ "Blue plaques". Rhondda Cynon Taf County Borough Council. Retrieved 20 September 2023.

- ^ "Blue plaques". Rhiwbina Society. Retrieved 20 September 2023.

- ^ "Transport Trust". Archived from the original on 7 June 2010. Retrieved 7 July 2010.

- ^ "Connecting Everyone with Chemistry". Royal Society of Chemistry.

- ^ "Blue plaques". www.iopscotland.org. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- ^ "Higgs unveils plaque in his honour". BBC News. 3 March 2015. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- ^ "Anne Lister: Reworded York plaque for 'first lesbian'". BBC News. 28 February 2019. Retrieved 19 July 2022.

- ^ "Rainbow Plaques". Studio Voltaire. Retrieved 25 July 2023.

Further reading

[edit]- Cole, Emily; Stephen Fry (2009). Lived in London: blue plaques and the stories behind them. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-14871-8.

- Dakers, Caroline (1981). The Blue Plaque Guide to London. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-28462-9.

- Eavis, Anna; Spencer, Howard (2018). "Risk and reputation: the London blue plaques scheme". In Pellew, Jill; Goldman, Lawrence (eds.). Dethroning Historical Reputations: universities, museums and the commemoration of benefactors. London: University of London Press. pp. 107–115. doi:10.14296/718.9781909646834. ISBN 9781909646827.

- Ito, Kota (2017). "Municipalization of memorials: progressive politics and the commemoration schemes of the London County Council, 1889–1907". London Journal. 42 (3): 273–90. doi:10.1080/03058034.2017.1330457. S2CID 149333953.

- Rennison, Nick (2009). The London Blue Plaque Guide (3rd ed.). The History Press Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7524-5050-6.

- Sumeray, Derek (2003). Track the Plaque: 23 Walks Around London's Commemorative Plaques. Breedon. ISBN 978-1-85983-362-9.

- Sumeray, Derek; John Sheppard (2009). London Plaques. Shire Publications. ISBN 978-0-7478-0735-3.

External links

[edit]- Open Plaques open register of historical markers

![City of Westminster green plaque at the Savoy Theatre, the first public building in the world to be lit entirely by electricity when it was fitted with the incandescent light bulb developed by Sir Joseph Swan in 1881.[45]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/91/Savoy_Theatre_%28Westminster_City_Council%29.jpg/127px-Savoy_Theatre_%28Westminster_City_Council%29.jpg)